Written by Andy McAusland | Download PDF

The purpose of this memo is to provide a high-level overview of the theory that underlies the Healthier Together and BeWellPBC mini grant activity. This memo won’t dive into the variety of flavors permeating local implementation, the specifics of successful mini grants or the colorful, inspiring people and personalities behind the ideas. The processes have local character, unique ways of celebrating, measuring, awarding, determining, scoring, publicizing their mini grants. This is vibrant territory well worth exploring in future memos.

Mini grants are an essential contribution to Healthier Together because innovation happens at the local level. Mini grants help launch small businesses, encourage professional development, and fund ideas that tackle some of our toughest challenges, like intergenerational wealth, health and well-being, family caregiving, and causes of trauma and violence. We are seeking to make sense of diverse and dynamic activity across 8 unique Healthier Together and BeWellPBC initiatives with 115 mini grants between them. Taken together, these mini grants offer 115 potential pathways to a healthier Palm Beach County. And that’s the heart of the mini grant concept. Small on an individual grant scale, sprawling in scope as a diverse collective. We are taking the platitude “sometimes less is more” and recognizing its correlate, “sometimes more is better.” (More mini grants.) Except when we mean “less is more”. (Relatively small dollar amounts per grant)

The theory base of mini grants is drawn from a number of sources, not all of which will be touched upon here. (Other memos in the future may explore additional material.) The touchstone is a paper by Nassim Taleb called “Understanding is a Poor Substitute for Convexity (Antifragile)” which explores heuristics (rules of the road) for stimulating a more dynamic research and innovation paradigm in the sciences. In order to cultivate systems that are “anti-fragile” and gain from disorder, (i.e. the pandemic), there must be many pathways and lots of trial and error. Convexity bias, or “antifragility”, is forged in an ecosystem of experimentation with high upside potential and minor downside risk.

In spite of diversity in form and function, mini grants have some commonalities across communities.

- There are many grants with small grant amounts.

- Individuals, non-profits and informal community-based orgs are all valid recipients.

- A locally determined process is conceived for locally determined priorities.

- Minimal constraints are imposed by the funder.

Practice vs Reality

As a preface, it may be helpful to consider the cognitive dissonance between the realities underlying our social ills – they are deeply entangled and impenetrable – and behaviors of the systems we’ve designed to combat those ills.

The Practice:

As grantmakers or funders, we implement strategies, fund research, issue directives and structure what we do based on four things:

- Our mandate – what do we exist to do?

- Our strategy – how do we accomplish what we exist to do?

- The body of information we have access to; i.e. what we know

- Our expectations regarding outcomes

The Reality:

Understanding and knowledge in the traditional sense lose relevance in complex environments because relationships between cause and effect are slippery. What we know drives what we do, while what we don’t know lurks around corners in the form of unintended consequences. What hides behind door number one may rapidly propel a project forward, while the shadow skulking behind door number two may disrupt in ways we couldn’t imagine.

- Outcomes cannot be predicted, making familiar value judgements such as “success”, “failure”, “high performance” and “poor performance” potential slippery slopes.

- Thinking and decision making is informed by massive and multiple variants of bias, subject to blind spots and tempered by the reality of bureaucratic pressures.

- Inordinate amounts of time are spent proving relevance, showing that what we do has an impact. (The accountability dance)

The Institutional Rationale:

- Success is attributable to dynamic ideas, skills and talents.

- Failure is attributable to “chalk it up to a learning opportunity”, “I just didn’t know”, “poor performance”, “failure of process”, “flawed execution”. (Or, worst of all, abject failure is spun as success for political purposes.)

We aren’t inferring that success is black and failure is red on a roulette wheel. We are highlighting the reality that randomness deserves it’s share, (often a significant share), of the credit and blame. It’s an easy target, a convenient dustbin for projects and ideas that don’t work out. Of course, when things go well, public relations will not draw up a campaign to credit randomness. Our social systems and work environments are not optimized for that manner of honest appraisal. Human systems often can’t risk acknowledging the role of chance, because to do so emphasizes the lack of control the system has often been designed to deny.

An Evolved Practice:

Picture a lost child, a frantic family and 15 neighbors ready to start the search. Rather than pile in a van together and execute a pre-planned route, they would most likely fan out and move in multiple directions at the same time. Tackling tough social issues in an uncertain environment presents a similar challenge. The winning strategy is to get as many people as possible into the streets, heading out in as many different directions as possible. For mini grants, we first accept the role of randomness. Next, we recognize that what we know isn’t as relevant as how implementation occurs (decentralized and local, turning over the power) and how much you do. (A lot!)

Convexity: High Potential Plus Low Risk

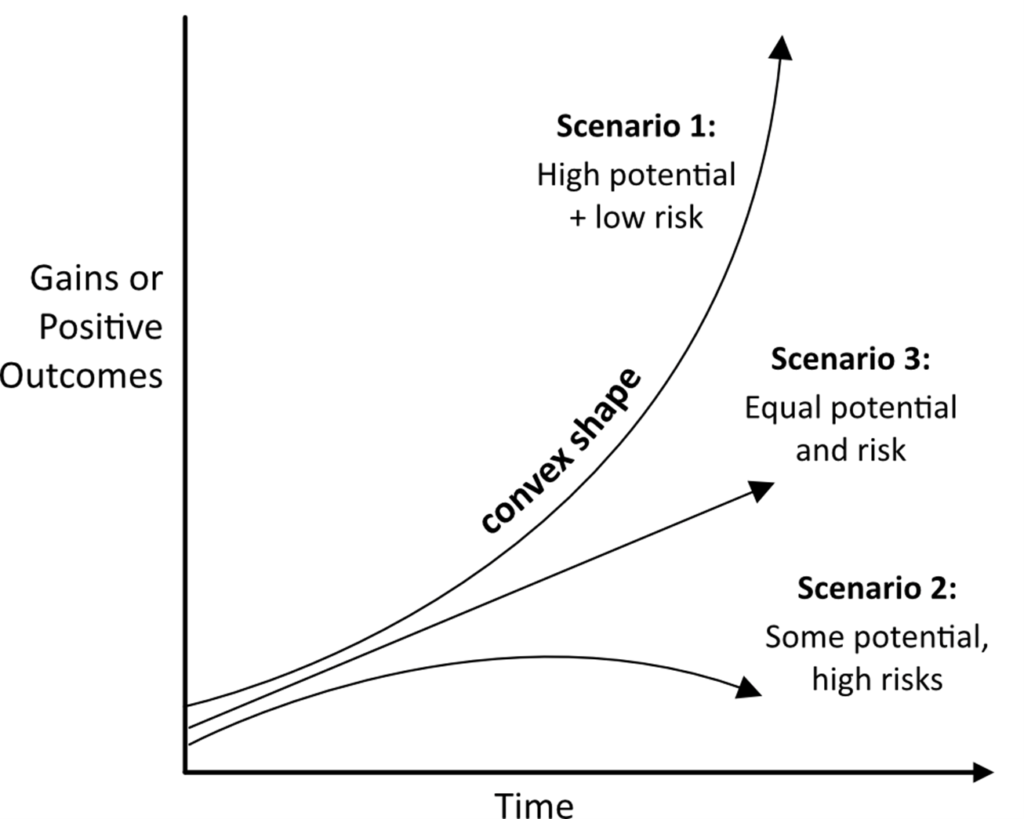

This goal of this description is to ease the reader into the concept of convexity bias, or “antifragile”. (For evaluators it may risk oversimplification.)

If you consider gains or successes over time, you can imagine a straight line moving slowly upward representing increasing gains as your project or intervention contributes to better outcomes (e.g., middle line in figure below). When projects involve greater risk, this line may decline or break (e.g., one step forward, two steps back). Instead of moving continuously upward, the line curves down. In contrast, when potential is high and risks are low, the line not only continues to move upward, it does so at an increasing rate. Convexity refers to the shape of this line, because it curves outward. The difference between the straight line, representing a scenario where potential and risk are equal, and the convex line is called the convexity bias.

This graph represents concepts at the heart of why mini grants are an important and legitimate strategy.

Scenario 1: Lots of trial and error, with failures and losses representing negligible impact to overall performance. The relationship between upside and downside is asymmetrical, i.e. upside potential of the approach is high, downside is low. In the human services world of grant and discretionary systems funding, approaches like mini grants are the analogue. The dollars per grant ratio is small, the quantity of grants is large and there is a willingness on the part of “the money” to decentralize and transfer control to trusted local agents. Time and energy investments into accountability – i.e. audits, reports, coordinating meetings, traditional communication etc. – is minimal. Time and energy can be spent in other ways – developing relationships, meeting in different ways outside of the “funder/fundee” identities, pursuing novelty, amplifying success, (doubling down on mini grants that show promise), experimenting with alternative tracking and evaluation methods that lose the traditional trappings of accountability, filling emergent gaps. We are working with what we call enabling constraints-meaning there is a shifting landscape of people, places, things and cultures we can take advantage of, within flexible boundaries, to encourage healthier communities. When failure occurs, it is on a small, easy-to-absorb scale. Meanwhile, the probability of successes increases as more opportunities are created to achieve it (and stay on the shifting pathways that lead to it).

Scenario 2: Applied knowledge with rigid rules in complex environments, no space built in for trial and error, and failure and loss have high potential downsides. In the human services world of grant and discretionary systems funding, “downside” is represented not only by money—but human costs in time, energy and missed opportunity. The centralized approach of our systems, concerned with the input, output, processing and analysis of large amounts of quantitative data, is the analogue. Data in this context is a form of static evidence base as opposed to a continuous feedback loop, even when establishing data feedback loops is a system’s intention. (Bureaucracies with hierarchies fueled by process, are not designed to respond to real time feedback loops with agility. There is a fundamental mismatch of skill set to presenting problem. Think a fish climbing a tree.) The data flow drives how systems operate, informs learned behavior and culture and is responsible for measuring bureaucratic check points, such as: Are we following the rules? Are we adhering to a defined theory of change and logic model? Does the data show that our programs have fidelity? Are we correctly processing data to determine success and/or failure and process improvement? Does a data cycle drive process improvement? The constraints of this system are rigid, meaning that governance is strong, centralized, all-encompassing with very little flexibility. When failure occurs, it is often chalked up to poor performance, poor process, or lack of adherence to process.

Scenario 3: Lots of trial and error with failures and losses representing high potential downsides. The relationship between upside and downside is symmetrical, i.e. high upside and dangerous downside are part of the equation. In the human services world of grant and discretionary systems funding, this is represented by the grand idea or “game changer” – an all-consuming strategy that requires orchestration of multiple and diverse partnerships acting in concert, joint buy in to a common agenda superseding individual ambitions or mandates, a belief that systems working together with a shared purpose is necessary to overcome deeply entangled and messy social issues. Activity can be based on trial and error but is often driven top down via strategy or “game changing” idea at a “too big to fail” scale. A deficit in requisite diversity of thinking, perspective and approach to spread the creative cognitive load and manage high degrees of complexity is a significant risk. Here, we are working under governing constraints, meaning there are rules, a common agenda, some absolutes, but also tolerance of trial and error within areas with flexible boundaries. Failure is attributed to lack of commitment amongst the partners, lack of bandwidth or inability of systems to coordinate effectively because of inherently siloed natures.

It’s important to emphasize these scenarios are assumed in human contexts under conditions of uncertainty. If one were charged with solving a complicated, engineering based issue like fixing the water system in Flint Michigan so it wasn’t pumping lead into the drinking water, scenario 2 would likely be the optimal approach. Local Palm Beach County collective impact initiatives Birth to 22 and BeWellPBC have sprung up as hybrid systemic and community based responses to issues requiring a scenario 3 approach – a coordinated and cross sector community effort. However, in human systems, under conditions of uncertainty, when faced with wicked social issues – what we know about a problem, or the theory on addressing that 10 problem, isn’t as important as how much we do, how we do it and the degree to which we limit downside.

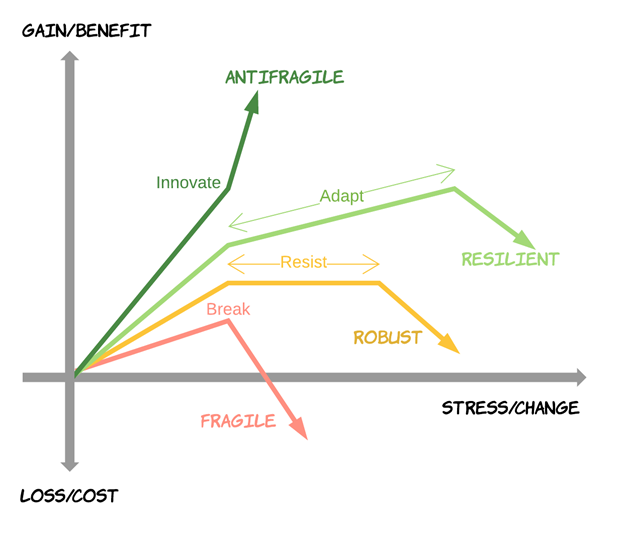

Hyper local mini grants are the most durable possible investments and a great potential response to an event like the pandemic. When implemented with proper intention, they can produce results in almost any imaginable social circumstance. In Taleb’s systems representation (in the following figure), mini grants are taking advantage of the convexity bias—i.e. they are antifragile and optimized to gain from the kind of disorder that causes other programs to fail or lose relevance as they sputter, or sit in a holding pattern, waiting for a return to “normality”. There will always be people, organizations and informal groups in the Healthier Together communities ready to respond, and mini grants have become an ideal mechanism in the Healthier Together ecosystem to engage, respond and innovate.

The pandemic presents a novel challenge and opportunity to assess our methods. Do we gain from disorder; do we thrive under conditions of uncertainty? Or are we fragile, frozen, at a loss because the plans and grand designs of a year ago have lost relevance overnight?

Rules of the Road for Antifragility

Taleb provides heuristics which can be leveraged – or practiced – to maximize the convexity bias, or antifragility in a system. These are general guidelines to keep in mind when thinking about information collection, sensemaking and presentation of mini grants. The Foundation has a long way to go in realizing an effective, systematic, yet unintrusive method for collecting and analyzing information from the mini grants. It’s not simple to catalog 115 flavors from 8 continents. However, here are some heuristics to guide the practice.

- More is better, and what we think we know is not as important, or as attributable to future success and failure as we believe it is. “Under some level of uncertainty, we benefit more from improving the payoff function than from knowledge about what exactly we are looking for. Convexity can be increased by lowering costs per unit of trial (to improve the downside).” Taleb, Understanding is a Poor Substitute for Convexity (Antifragile)”, 2012. The takeaway: Perhaps we place too much stock in what we think we know when the optimal strategy is to iterate ideas rapidly, inexpensively, with intentionality.

- The more grants made, the more diversity of thought and approach within mini grants, the more we limit failure. (Represented by loss of time, energy, money, morale, distraction, etc.) Big initiatives that suck all the air out of a room have high downside with regard to time and energy loss, poor morale, a lack of agency, forced passion, multiple cultures clashing, etc. In conditions of uncertainty, “smaller units can combine and recombine in different ways and are more agile in nature”. (Snowden, Rancati, Managing Complexity (and Chaos) in Times of Crisis, 2021) The takeaway: Be more concerned with limiting failure with spread bets than striking it big with a “game changer” on a major strategy, system or program initiative. The overarching companion heuristic, “local, local, local” is worth over-emphasizing.

- The big payoff can’t be predicted and is more likely attributable to chance then skill or detailed planning when it happens. For example, while building magnatrons and working on radar equipment, Perry Spencer invented the microwave after he noticed candy bars melting in his pocket. This was a novel and tangential path, stumbled upon by chance, previously missed by others who noticed the phenomenon but never bothered to investigate. There was no ribbon cutting and project launch with a Governor’s keynote commemorating pursuit of the T.V. dinner. Spencer was actually hard at work trying to help win World War II when he made the novel connections leading to his invention. An important aspect to the 13 parable is Spencer being allowed to work in conditions that encouraged novelty and innovation. Obviously, Spencer was a gifted inventor, his skill and knowledge are essential ingredients here. The question we should ask ourselves is: How much talent has been missed, misused or not given an opportunity over the years in service of the status quo? The takeaway: In certain circumstances, put away the notion of “this idea is a game changer” and create conditions to emergent solutions. That is where the Perry Spencers’ and their ideas hide, often in plain sight.

- Flexibility in process and not being locked into plans is crucial. For example, during the pandemic, Healthier Neighbors was able to pivot the mini grant process to a virtual environment. Instead of in person events, Healthier Neighbors used Facebook Live. The takeaway: Resist the culture that dictates being firm in conviction no matter what; resist attachment to ideas and reserve the right to change your mind.

- Antifragility is a product of people, or combinations of people and less about programs, and finely-honed strategic plans. “Technologists in California ‘harvesting Black Swans’ tend to invest with agents rather than plans and narratives that look good on paper, and agents who know how to use the option by opportunistically switching and ratcheting up.” (Taleb, “Understanding is a Poor Substitute for Convexity (Antifragile)”, 2012) The takeaway: People connected to a local context, who take the health of their community personally, are more likely to dynamically challenge societal issues of relevance than an institutionally-driven plan based on knowledge and theory. Also, there is great power in agency. The singular grand design is the domain of the elite and offers little in the way of agency for participants. On the other hand, 115 mini grants offer 115 different paths to increased agency in community solutions. This is a difficult-to-quantify yet powerful concept.

- Theory is born from practice and rarely does the opposite occur. Yogi Berra perhaps put this best when he said, “The only difference between theory and practice is in theory, there is no practice, but in practice there is”. In complex systems, practice is emergent and exaptive; there is no “best” practice. “Exaptation in evolutionary biology indicates the repurposing of an artifact, trait, or a module developed through natural selection……In organizational terms, exaptation indicates a process of radical repurposing of roles, processes, paradigms, values. It is a state of action that emerges after critically observing the present while (sometimes frantically) creating the structures and the conditions for organizations to adapt”. (Snowden, Rancati, Managing Complexity (and Chaos) in Times of Crisis, 2021) The staid, stable cadence of grant funding and activity will not typically evolve dynamically to become the mother of invention. The takeaway: Local agents embedded in context, fiercely committed to place, have distinct advantages over experts dependent upon the evidence of a narrow field. This is not meant to dismiss experts out of hand, but more an acknowledgement that understanding the territory is an essential contribution, often trumping the theory. Taleb points out that the history of invention and innovation is populated with tinkerers and hobbyists working in everyday contexts. On another note, the grant making world does not need practice drawing up elaborate frameworks and mechanisms for instituting evaluation and capturing outcomes. Traditional accountability and grant application processes are habitual. Letting go of control and actively practicing decentralized approaches to funding takes courage, even though ironically, the actual downside risk is decreasing. The art lies in a new practice of scaffolding sensible guidelines and structures, that may be temporary, that maintain local flexibility.

- Albert Einstein allegedly said: “Keep things as simple as possible, but not any simpler”. Embracing simplicity without being reductive is an artful balance, with many corollaries spinning off of the principle. If we stay small and local (mini grants), we have a far better chance to understand relationships and opportunities at play in a system. The larger the scale, the bigger the project, the more complex and impenetrable the resource conflicts, clashing of cultures, relationships, agendas, and politics. “Organizations designed for stability rarely survive the transit into unstable, unpredictable times as long-term objectives and planning cycles are unable to respond to sustained change”. (Snowden, Rancati, Managing Complexity (and Chaos) in Times of Crisis, 2021) This is getting into implementation practice in times of uncertainty, another topic for another time. Relaxing constraints, decentralizing decision making authority and cataloging what works is far simpler than changing an immense and complicated system. “We seek to to enable the emergence of of resilient solutions with with a low level of risk (high informality) and energy (high spontaneity). (Snowden, Rancati, Managing Complexity (and Chaos) in Times of Crisis, 2021)

- Mini grants offer an opportunity to better catalog negative results. We have not yet explored a systematic way of doing this and it is a priority to focus on in the future. Obviously, the more you know about what doesn’t work, the closer you get to, or the more you can refine, the ideas that do. As we begin to create sensible constraints and mechanisms for collecting relevant information from mini grants, we will contemplate ways to judge and record “negative results,” “good idea before it’s time,” “good idea,” etc. Thus far, we have emphasized the necessity of local implementation and local control for a local process. How we capture this blizzard of activity is the next challenge. There is no shortage of tools, forms and guides to review, exapt and glean ideas from. While we are open to “the market”, we remain skeptical that application of someone else’s tool or idea will offer an easy solution. There is often a need for bespoke tools in unique, context dependent environments.

Conclusion

An overarching purpose of mini grants is to fuel innovation and improve health and well-being in a complex environment, one characterized by ever-changing causal pathways to success. In order to succeed, the concept of convexity is highly relevant. This refers to the scenario in which the potential of one’s endeavors is high while the risk is low. Mini grants meet this criterion by comprising many grants with small grant amounts, effectively “casting a wide net” and making failure small and easy-to-absorb. This increases the convexity bias, which is the additional gain experienced as benefits begin to outweigh risks.

While Part I of Mini Grants Theory, More is Better, has provided an overview with a focus on convexity and antifragility (concepts explored by Nassim Taleb), Parts II and III may continue by addressing the following topics:

- The nuts and bolts of implementation. How do we respond to chaos and crisis, or how can we best implement in complex environments per Dave Snowden’s “Managing Complexity (and chaos) in Times of Crisis?” How do we respond and manage to allow for processes like mini grants to succeed in complex environments? This topic will also touch upon the different context of chaos and why taking firm, centralized control during a true crisis is preferable.

- All of the color, activity and diversity of locally determined processes and 115 mini grants.

References

Taleb, Understanding is a Poor Substitute for Convexity (Antifragile), 2012 https://fooledbyrandomness.com/ConvexityScience.pdf

Snowden, Rancati, Managing Complexity (and Chaos) in Times of Crisis, 2021 https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/managing-complexity-and-chaostimes-crisis-field-guide-decision-makers-inspired-cynefin-framework